Can Intrinsic Rewards Save RL?

I have always been uneasy with how reward is modeled as part of the environment in reinforcement learning, but I felt somewhat unqualified to question it. I was recently glad to find like-minded friends on X (Yoav Goldberg and Hadi Vafaii) who shared my view and articulated it far better than I had in my own mind 1 2. I first summarize the argument, and then argue that a convenient patch often used to address this concern—intrinsic rewards, as they are commonly formulated in terms of sensory surprise or prediction error—is inadequate to explain curiosity in humans.

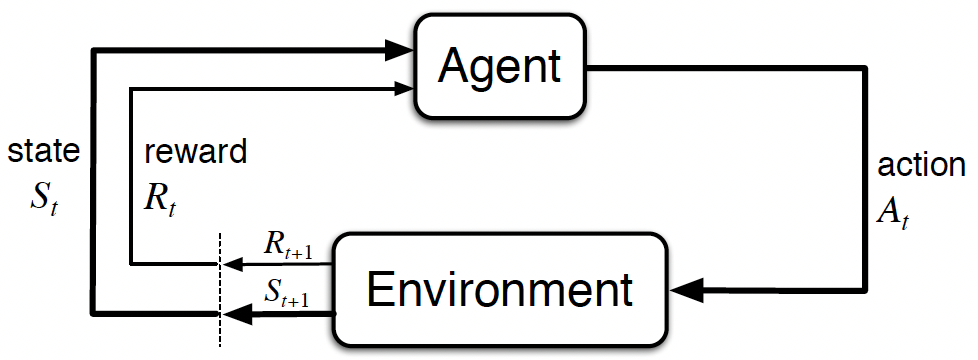

The following is the classic figure from Reinforcement Learning by Sutton & Barto:

At each time step (\(t\)), the agent takes an action (\(A_t\)) in the environment, leading the environment to transition to a new state (\(S_{t+1}\)). The environment then emits a scalar reward (\(R_{t+1}\)), which the agent receives as given. The agent’s objective is to choose actions over time so as to maximize the cumulative reward it receives in the long run.

The main point of contention is this: should rewards be modeled as part of the environment or as part of the agent?

In the real world, no animate being has direct, unadulterated access to the environment—everything is inferred. The brain receives spikes, or action potentials, at its synapses from other neurons, and from these it infers what is “out there.” For example, photons exist; color does not. Color is an inferred quantity, constructed by the brain from incoming sensory data (an insight also known in philosophy as the theory-ladenness of observation 3). Likewise, rewards must be inferred by the agent by observing changes in the state of the world 2. That is, the reward mechanism should be modeled as part of the agent rather than the environment.

This view goes directly against the basic building blocks of RL as described in Reinforcement Learning book:

“We always consider the reward computation to be external to the agent because it defines the task facing the agent and thus must be beyond its ability to change arbitrarily.”

At this point, a common and convenient patch is intrinsic rewards—curiosity, surprise, or other domain-agnostic intrinsic signals. Now, notwithstanding that if reward is completely intrinsic to the agent then it already breaks the fundamental assumption of RL that reward must come from the environment 2, I argue that the prevailing conception of intrinsic motivation itself is inadequate to explain human curiosity.

The most common formulation of intrinsic reward in RL is based on sensory surprise, prediction error, or closely related notions 4. The core idea is that the agent seeks sensory novelty in the environment and explores it. For example, a human infant might experience sensory surprise upon noticing a new toy, a bright light from a novel source, or an unfamiliar rattling sound, and would be motivated to explore it. Rich Sutton, in his recent talks on the OaK architecture at RLC’25 5 and NeurIPS’25, also alludes to this idea of creating an option upon the occurrence of an intrinsically rewarding event, using similar examples of infants noticing new toys or sounds.

However, I believe such forms of intrinsic motivation—based on surprise or predictability—are almost the opposite of the curiosity observed in humans. Humans are often curious about the most mundane and omnipresent phenomena, such as the night sky filled with stars, which has motivated scientific curiosity for millennia. From the perspective of surprise or prediction error, the night sky is among the least surprising and most predictable features of the environment. An agent driven by prevailing notions of intrinsic motivation, if dropped into the real world, would be least curious about it.

As another example (courtesy of Rosa Cao), imagine a miracle: a stone that endlessly produces a constant, fixed-trajectory stream of blood. After observing it for a day or two, the phenomenon becomes perfectly predictable and generates no sensory surprise. An agent driven by prevailing conception of intrinsic motivation would therefore have no reason to further explore it. A human scientist, in contrast, would find this event increasingly perplexing with each passing day and might devote an entire lifetime to explaining it—just as scientists have done, and continue to do, with the night sky.

In both cases, human scientists are driven by a quest for explanatory understanding rather than mere predictability. Prevailing conceptions of intrinsic motivation do not naturally give rise to a drive for explanatory understanding, which is arguably the hallmark of human curiosity. Of course, one could imagine alternative intrinsic motivation functions that do lead to a quest for explanatory understanding; what I want to highlight here is the distinction between two very different kinds of curiosity—one based on sensory surprise, commonly observed in animals and human infants, and another based on the pursuit of explanatory understanding, characteristic of human scientific inquiry.

(Thanks to Hadi Vafaii and Rosa Cao for discussions related to this.)

References

-

Burda, Yuri, et al. “Large-scale study of curiosity-driven learning.” arXiv preprint arXiv:1808.04355 (2018). ↩

-

Rich Sutton, The OaK Architecture: A Vision of SuperIntelligence from Experience - RLC 2025 ↩

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: